When it comes to storytelling, no matter what the medium, the setting plays an important part as much as the characters. For a good percentage of Marvel comics and movies, that can be the Big Apple. In DC Comics’ Batman, Gotham City. For Sega’s Yakuza series, that is largely Kamurocho. In Star Wars, that happens to be a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away. Without a world for our characters to live in, we essentially have nothing to project our cast and to a certain extent, ourselves into. When it comes to anime, the rules of a great setting more or less applies to what you see in other forms of storytelling. As for anime (and manga), it expresses the freedom of visual storytelling to distinguishing levels of creativity.

Unfamiliarity

Anime (and manga) challenges the imagination like no other. With Dragon Ball Z, it’s how it expresses action like we’ve never seen before, but when it comes to introducing us to its world, it shows how everything from vehicles to houses are portable with capsules that fit right into your pocket. While it is only a side-gimmick, this particular quality helps provide the audience a foundational identity to the world these characters live in. Though the world is in constant danger from intergalactic threats, they have distinguishing conveniences that you don’t see anywhere else, and its cast and technology that create its world give the audience something to stimulate its imagination. Beyond that, the series takes us across the galaxy, the afterlife, and a multiverse showing how its setting can progressively expand to new territories thus giving our characters newer and more unique challenges due to them being unfamiliar.

The rise of Isekai anime have all done a great job of pointing out the quality of unfamiliarity since that is the genre that easily best exploits it. From Fushigi Yuugi to Tate no Yuusha no Nariagari, any ordinary teenager forced into an unfamiliar world, especially when it doesn’t resemble their own culture and values, can be an overwhelming experience. While the idea can be exciting, unfamiliarity with the area and the people can be overwhelming, and whatever can be going on there in terms of the mythos and/or political situations of that world, tend to consequently fall on the shoulders of the main character(s) for better or worse. Regardless, the main characters have to bear the responsibility of the role they’re given, and those experiences naturally develop them to become better people. And what better challenge than surviving an unfamiliar world as its appointed savior?

Educational Merit

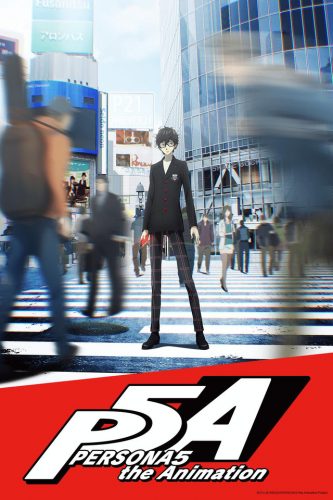

For international audiences, the use of modern (or ancient ) Tokyo from Sailor Moon to Persona 5 provides them a distinguishing sense of unfamiliarity since they obviously don’t live there, and/or have yet to visit. To many non-Japanese audiences, Tokyo or any other city in Japan can be exotic, and such anime does an excellent job of portraying its highlights to international and domestic viewers alike. Through anime, you can feel how exciting and overwhelming Tokyo or other cities in Japan can be, and depending on the anime, its provided setting (in definition to both place and time) can provide something educational.

For Persona 5, it gives audiences an opportunity to experience Shibuya, a trendy district for teenagers. Through Steins;Gate and Akiba’s Trip, they give audiences a taste of Akihabara, the Heaven for those that are lovers of Japanese pop culture. Or through Grave of the Fireflies, with its use of the final days of World War II, audiences of all backgrounds are given a semi-biographical account as to what was happening in Japan and how its children were affected by it. For High Score Girl, audiences that are hardcore gamers can learn what the gaming scene was like in the 1990s in Japan. For example, most non-Japanese gamers think of the 1990s Console Wars between the Genesis (or the Mega Drive in your respective home nation) and Super Nintendo (or Super Famicom in Japan). In Japan, it was between the Super Famicom and the PC Engine (or the Turbo Grafx-16), and despite the Saturn’s failure in North America, non-Japanese audiences can learn how the Saturn was actually a success in Japan.

Final Thoughts

Through Sci-Fi settings, this is probably the most effective medium in which audiences can get something more valuable in a moral definition. While Sci-Fi tends to take place in the future whether it would be in space or a dystopian Earth, they tend to be a critique on modern society and/or a pre-cursor for what is to come. For the original Gundam series, it was obviously a critique of World War II, and with 00, it was a reaction to what was going on in the Middle East.

When you trace back to when the original Ghost in the Shell debuted, it was certainly ahead of its time and that quality is why it still continues to prosper. It’s not just the original 1995 movie, but if we could count the manga that debuted in 1989, it predicted how technology would involve, most emphatically the internet and how society would be dependent on it.

Lastly, with Akira (which is confirmed that it’s getting a new anime), putting aside that the original film predicted the 2020 Olympics or how Tokyo would become this neon light city, it was a reflection as to how a fraction of the youth of Japan were joining motorcycle gangs in the 1980s and warned us of Japan militarizing. With the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (despite the name, it’s a right leaning party) wanting to remilitarize the nation, Akira’s setting has done an excellent job of being ahead of its time in more ways than one.

When it comes to the setting, it does provide something unique, but in the end, its qualities provide motivation for character development, or something strikingly relatable.