It was subtle, delicate, and gentle. It highlighted the strengths of the film medium, a mixture of visual, writing, sound--art. It gave perspective through someone’s eyes, made viewers accustomed to a world where voices were quiet but emotions were loud. From the pitter patter of footsteps to the oboe’s melodic goodbye, so much was said without words.

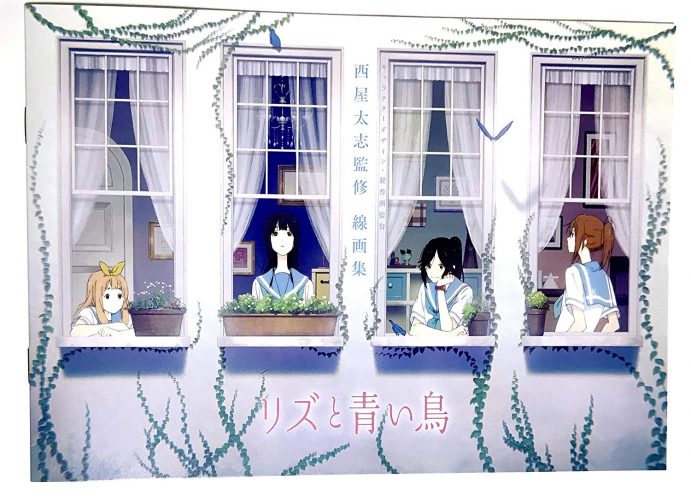

Liz and the Blue Bird is “visual literature,” an excellent showcase of how a picture can say a thousand words. For this article, I want to introduce some concepts that will help viewers understand Liz and the Blue Bird. By focusing on the shots used commonly in dialogue and teaching concepts of nonverbal communication, I hope I can share with you both my appreciation of cinematography and this film.

Shot/Reverse Shot, a Fundamental Tool of Capturing a Response

One of the most common shots is a pair: the shot/reverse shot. This is a film technique where (typically) a character is shown talking to an offscreen character, then the camera cuts to the other character’s response.

A shot/reverse shot can give viewers added nuance: a visual response. This allows viewers to judge the subtext (underlying meaning) of dialogue because information is conveyed through more than words. These types of shots are not only common, they’re one of the fundamental tools directors use to convey dialogue/communication.

In conjunction with good writing/dialogue, a good shot/reverse shot can unveil things such as intentions, psychology, behavior, perspective, and so on. If a shot/reverse shot is done without thought--done in such a way that the shots exists by convenience--then the director can hurt a work’s pacing. The effective management of time can lessen the burden of a script, allowing for a cohesive synergy between visuals and writing.

Body Language as Communication

Body language is a type of nonverbal communication that uses physical responses to divulge information. Examples of this can include physical distance between a person, eye movement, facial expressions, and touch. To clarify, this does not include sign language, as sign language has words.

Within the study of Communication, there is also debate on whether involuntary/unintentional nonverbal physical responses are included as communication. Examples of these would be a cough from sickness or your stomach growling.

However, in film, especially animated films, every aspect of nonverbal communication has some degree of intention. Even if an actor coughs from sickness, it is up to the director and editor to leave that in. Furthermore, in film, nonverbal communication can be expanded. Since a film is a combination of the arts, sound/music can be communicative of one’s mental state. This opens up an avenue of language that viewers can interpret and directors can use to communicate their work.

How to Personalize a Response: An Unspoken Distance

To help viewers understand Mizore, Naoko Yamada uses shot/reverse shot, body language, and sound/music. The scene after the fairy tale introduces viewers to many of these concepts and acts as a guide for the audience.

This scene begins with a close up of Mizore’s shoes, the audible sound of her footsteps clacking through the silence. Mizore sits down, and we see her bide her time, fiddling with her hands and clapping her shoes together. She breathes a heavy sigh, possibly an expression of exhaustion or anxiety. She sees someone in the distance but only their shoes. She picks up the courage to look higher. It’s not the person she’s waiting for. Her eyes lower again as this person passes by.

But then she arrives. The music starts just as her footsteps enter into the scene. Mizore’s former disinterest melts away. To get a better look, she twists her body, the energy of her movement pans the camera into the next shot: a clear view of Nozomi. Without words or explanation, you know how Mizore feels.

But the scene moves forward at its own pace, inconsiderate of the person who follows. As Nozomi leads Mizore towards the band room, a certain distance is maintained. This distance gets referenced (visually), and how it’s used in the film cues you about the fluctuating nature of their relationship. Originally, this distance might seem unintentional--Mizore even remembers how they walked in the past, implying this is how it’s always been. As both characters become aware of this divide between them, this distance becomes verifiably intentional. This is nonverbal communication.

Within the walking scene, there are also other cues. By priming the viewers with sound (footsteps) from earlier, the off-sync footsteps create a strange rhythm. For the rhythmically-challenged (this includes me), Nozomi’s ponytail sways side-to-side like a metronome, allowing viewers to distinguish the beats. These sounds reinforce an idea: these two, while friends, are not in sync with one another.

This concept gets reinforced by the images of obstacles and the timing of the cuts (transitions) between each shot. These obstacles include the middle of doors, pillars, divisions on the wall, and even elevation. Furthermore, these obstacles serve as “ending points.” Once Nozomi has reached a certain distance, Mizore barely squeezes into the shot. Mizore can’t even reach the “finish line” of the shot before Nozomi leaves.

If viewers are confused by the walking scene, once the characters reach the music room, the words “disjoint” fades in and out to white. These two are the first to the music room, and they sit in the front row--their skill as musicians place them there. It is here we get more dialogue, and it’s here where shot/reverse shot is utilized.

Mizore breaks the silence; “I’m happy.” The shot is from her side without Nozomi in the frame. The shot cuts to a wide shot from Nozomi’s side. You see her confusion as she turns her head towards Mizore. When Mizore looks back, the next shot is isolated: Nozomi is in the picture, but Mizore is out of the picture. Nozomi then says, “You too?” We get a reverse shot, a closeup from Mizore’s side. She leans her head forward, happy that Nozomi feels the same way.

We then see Nozomi once again isolated and shot from the side. “I’m happy, too,” she says while brushing her hand against the sheet music. A reverse shot of Mizore, this time even closer--her eyes dance in anticipation. “This piece is amazing.” Nozomi finishes with a closeup of her side. But then…

Distance

“I’m so glad this is our free piece,” she says. The shot, still focused on her side, is now much farther out. We get a reverse shot of Mizore, no longer a closeup. After all, the “closeness” of their conversation has faded away. Nozomi didn’t understand Mizore’s happiness. Fast forward to the next scene. Other band members enter in as pairs. They greet both Nozomi and Mizore, but always in the shot, the distance between. Everyone else is close. When Mizore looks away, you know what she’s thinking, “Why is everyone close, but I feel alone?”

Final Thoughts

At first, this film seems soft-spoken, its inner voice tucked away much like the shy protagonist. However, beneath its exterior is an emotional fiber, connecting viewers to a dense, empathetic story.

Liz to Aoi Tori (Liz and the Blue Bird) was my favorite animated film in 2018, and I hope with this article, I could share with you the reasons why.